If you’ve got money, time, and know-how, then you can make more money by investing. The more you have of any of those three ingredients, the more money you can make. I don’t have a lot of know-how, but here’s a little to get you started.

Saving vs Investing

If you have some money, and you want to keep it, that’s saving. If you want to use the money to make more money, that’s investing.

Saving means keeping your money safe, so it’s still there when you need it later.

Investing means taking your money out of the savings account and putting it to work — making an extra effort and perhaps taking a chance with your money. Investing usually (but not always) implies doing something where you’re not 100% sure about the pay-off, but you’re pretty sure the reward will make it worthwhile.

It’s possible to start investing without risk. As discussed in the earlier “Saving” article, there are ways to improve your interest yield beyond what you can get in a savings account, without risk. Those other savings alternatives could probably be called “investments”. In fact, “GIC” stands for “Guaranteed Investment Certificate”, and it has the same guarantee as a savings account. So you’re taking money out of your savings account and putting it to work, but doing so without risk.

(top)

Saving your savings from inflation

Investing isn’t just about getting greedy trying to make money without working for it. In the long term, you need to address the challenge of inflation.

When interest rates are lower than inflation, your “long-term savings” won’t stay truly safe for the long term — their spending power will erode.

If you park $1,000 in a savings account earning 1% interest for ten years, and the inflation rate averages 4% over those ten years, then you’ll end up with $1,105 in the bank, and $1,000 in living expenses will cost $1,480. (I used this online calculator.) The gap will be much more dramatic if you do this calculation for 40 years: $1,489 saved vs $4,801 living expenses.

On the other hand, if interest rates exceed inflation, then if you have a healthy savings account balance, and you’re able to access decent savings interest rates (see “Saving”) then you might figure it’s not worth taking any risk.

Refer to the “Saving” article for ways to get the best possible interest on your savings without introducing risk. That’s a good place to start. Currently, it looks like the best available interest rates are higher than the current rate of inflation. If that continued for years, you could conceivably save for a modest retirement without any risk.

But you can’t count on interest rates staying ahead of inflation. The government raises interest rates to slow down inflation, and reduces interest rates to boost the economy (ie speed up inflation). (See Understanding our policy interest rate—Bank of Canada) But it’s complicated. There are other factors. The government can only influence—not actually control—both interest rate and inflation rate.

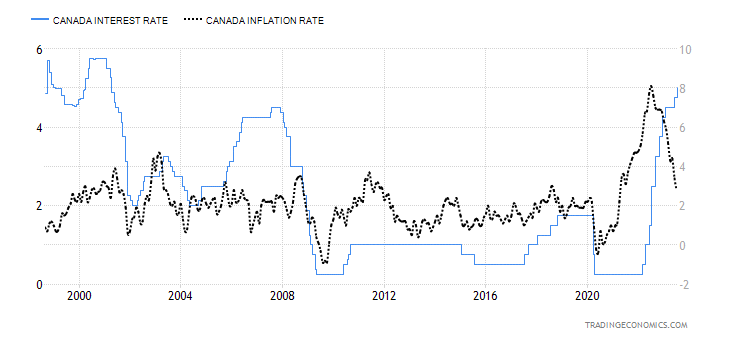

Here is a graph showing that interest rates have exceeded inflation by a significant margin for a couple of multi-year intervals around 2000 and 2008, but since then, interest rates have lagged inflation—until very recently.

https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/interest-rate

If you want your long-term (retirement?) savings to keep up with (and hopefully to exceed) inflation, then both you and your money have some work to do.

(top)

Investment options beyond savings

When you tell an investment broker that you want to invest your money, what they hear you saying is that you want to buy stocks and bonds. That’s what the world of investment is built on. Your investment portfolio will generally contain two main asset classes:

- Stocks (Equity)—you buy a piece of a business and profit from the success of that business (high-risk, high-reward)

- Bonds (Debt)—you lend money to a business (or government) and they pay it back over time with interest (low risk, low reward)

There are other things, like real estate, gold & silver, and other things that I know nothing about, so I won’t talk about them. Collectively, everything else is called “alternative investments”.

(top)

Stocks

The Stock Market allows a business to sell shares of their business to raise money to build that business. When you buy one of these shares, you’re betting on the success of that business because now you own part of it. The value of your share rises and falls with the value of the business. When your share value rises, you can sell it at a profit, or you can hold on to it if you think it will go higher. This is one way to make (and lose) money in the stock market.

There is another way to make money with stocks. Some companies distribute a share of their profits to their shareholders. These payments are called dividends. Although there’s still no guarantee that you’ll make money with these stocks, the dividends are paid on a schedule and will generally continue to flow even though the value of those shares on the stock market continue to rise and fall with the market.

Although choosing individual businesses in which to invest is a difficult and risky proposition, stock market investors are collectively pretty much guaranteed to make money investing in the stock market in the long run. The truth is: the game is fixed.

We live in a capitalist economy, and the whole thing is based on successful businesses making money. When business makes money, people have jobs. Everyone pays taxes, and that keeps the government afloat to handle the responsibilities that businesses can’t be relied upon to take care of. This is why the government concerns itself with interest rates and economic growth. Economic growth means successful money-making for everyone.

(Why Do We Think Stock Markets Will Go Up Over Time, Anyway? — wealthsimple.com

(top)

Bonds

Bonds are essentially loans, and as such are sold with maturity dates corresponding to the length of time the money is being borrowed. Unlike personal loans, the full amount of a bond is held until maturity and then paid back all at once. Interest is paid periodically over the term of the bond.

Both business and governments (all levels) sell bonds to raise money. Their interest rates reflect the current market rate, but can be higher or lower depending upon how risky or secure they are. You can get higher interest rates by choosing bonds from riskier borrowers. Everything is great if they pay up. But they might not. If you value security over the rate of return, you can select bonds with a better credit rating. Government bonds, for example, are safe enough to be considered risk-free.

If you buy a bond and hold it for its full term, you can consider it to be a secure investment, conditional only upon the fulfillment of the borrower’s obligation to pay up.

If you buy a long-term bond, your money will be tied up for a long time, so you want to consider whether the interest rate now is still going to make sense years from now. (10- to 30-year bonds are not uncommon, and the government of Canada has issued 50-year bonds!) If you hold on to it, you are guaranteed (by the borrower) to get everything you signed up for. But if everyone else is now getting a much higher rate of interest on their investments, you will likely be jealous of them.

This (being stuck with old bonds that lose value in the current market) is the second kind of risk entailed in investing in bonds.

But it follows that there is also a corresponding possibility of reward because if the market interest rates have gone down since you bought your bond, everyone else will be jealous of you because your old bonds have gained value in the current market.

Because your old bonds still perform exactly as promised, this fluctuation in their current market value is just academic, and you gain or lose nothing if you continue to hold them to maturity.

But investors like flexibility more than commitment, so they came up with the idea of a used bond market (“secondary market”). This is where people can unload outstanding bonds that they don’t want any more, either because they need the money now, or because the interest rate is no longer attractive. Or because the bond issuer is having financial troubles and their credit rating has gotten worse. Or because the interest rate on your bond is much better than the current market is paying, and you want to cash in now.

The secondary bond market reflects the current attractiveness/value of bonds that were issued some time ago. Since these used bonds will continue to pay the original interest payments and repay the face amount at maturity, the selling price reflects the current value—which can be either more, or less than what the original buyer paid out.

Thus, if you are unable or unwilling to hold your bond investments to maturity, you can no longer consider them to be a risk-free investment. By selling them before maturity, you might make more money, or you might lose money by selling the bond for less than you paid for it. (But it won’t be a total loss unless the bond issuer goes bankrupt and defaults.)

If you buy a used bond on the secondary market and then hold it to maturity, then you are guaranteed (by the original bond issuer/borrower) to get what you bought, and it is still (relatively) risk-free. You know what you’re paying for it, and you know what interest and principal you’ll be getting over its remaining life. When you hold a bond to maturity, It’s really not much different than buying a GIC.

(top)

Balance

As described above, the government influences interest rates as part of its efforts to manage the economy — raising interest rates to slow down inflation, and reducing interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending.

As a result, you can buy yourself some protection from stock market volatility by keeping part of your investment portfolio in bonds—or other interest-bearing investments/accounts.

Interest rates and the stock market often exhibit an inverse relationship. Higher interest rates tend to put downward pressure on the stock market by increasing the cost of business expansion. Lower interest rates can make it cheaper for businesses to expand, while simultaneously encouraging investors to move money out of savings and into stocks to try for better return on investment.

It’s complicated, though. For example, rising interest rates result in higher rate of return on new bonds, but lower market value for previously-issued bonds already in the market.

Although you can’t count on offsetting rises-and-falls, bonds can still be the safe and sensible—generally less risky but also less rewarding—component of your portfolio, serving as ballast to soften extreme swings in the stock market.

Investors tend to “balance” their portfolios between stocks and bonds according to their appetite for and tolerance of investment risk.

A common ratio for a “balanced” portfolio is 60% stocks and 40% bonds. A higher percentage of stocks would be considered more aggressive, and a lower percentage of stocks more conservative. (The most important factor in choosing the right balance for your portfolio is how much time you have before you need to take money out.)

When you’ve decided on the balance ratio, and invested the appropriate amounts in stocks and bonds, you will find that eventually your stock/bond value ratio will change because the two kinds of investments grow or shrink at different rates. This makes sense because that’s exactly why you’re doing this. You’ll need to “rebalance” your portfolio from time to time by selling investments on one side and reinvesting that money in the other side to bring them back to your desired balance. Ths rebalancing helps you “buy low/sell high” because you end up selling investments that have made more money, and buying investments that have become relatively cheaper.

For investors interested only in long-term growth, it can make sense to ignore bonds and go all-in with stocks. That’s where the dramatic results can happen, and you can afford to wait out the bad times. But if you might need some of this money in less than ten years, then you’ll want to protect some of it in fixed-income investment. You want to be able to pull money out without taking a loss. In fact, though, you’ll probably still want to rebalance your portfolio after taking money out, because you want to keep yourself positioned for the long term.1

(top)

Investment Pooling: Mutual Funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

Stock Funds

Buying individual stocks is tricky. You might want to try it on a small scale for thrills, but with your life savings, you ought to leave this sort of thing to professionals that you trust. And that will cost you because they’re doing it to make money. (And they don’t guarantee their work: you still might lose money.)

Mutual Funds allow you together with a group of many other individual investors to hire experts to invest your money as part of a pool. You buy shares in this “mutual fund”, they invest it for you, and pay back the proceeds as “distributions” either in cash or reinvested in additional shares of the fund. The share value of the fund can rise and fall in value as the investments it holds become more or less valuable in the marketplace.

(top)

Index Funds

Market performance is measured by “indexes” consisting of a large selection of specific stocks designed to be representative of the entire stock market, or a particular subset.

At some point (I think it was in the 1970s) somebody noticed that the stock-pickers doing the investing for mutual funds didn’t generally produce results any better than the indexes used to monitor stock market performance.

The big idea was to take the expertise / guesswork out of investing, and simple run a mutual fund that blindly and automatically purchases (for the fund holders) all the stocks that make up a particular index. Because the indexes are designed to represent a broad and balanced picture of the entire market, the risk of making bad individuals stock choices was no longer an issue. All the work involved in investigating and evaluating stocks was eliminated, and this greatly reduced the expenses of the fund. Over time, investors and their advocates noticed that this kind of investing strategy tended to produce better results — at lower cost — than achieved by expert stock pickers.

(top)

Bond Funds

Fixed income investing isn’t as risky as equity investing, but there are plenty of investors who prefer to leave as much as possible to the experts. So bond mutual funds exist to meet that demand.

The managers of a bond fund purchase bonds that meet the criteria (length of term, credit risk, sector, etc) of that particular fund. They continue to buy bonds to replace bonds that mature, and to invest new money coming in when customers buy more units of the fund. They may need to sell bonds to raise money when customers sell units of the fund.

Because the fund holds countless bonds with different start and end dates and interest payment dates, there is a fairly steady stream of interest payments. The fund accumulates these interest payments and then pays them out to the unit holders as (usually) monthly distributions.

The point-in-time unit value of a bond fund (used to price unit purchases and redemptions) is determined mostly by the current secondary bond market value of the bonds held in the fund. Thus, there can be fluctuations in the bond fund unit prices that have nothing to do with the actual interest being paid.

When you invest in bonds in a bond fund, you lose the guaranteed return that comes with holding bonds to maturity. You have no control or even knowledge of whether bonds are being held to maturity and when the time comes to cash out, you’re essentially selling bonds blindly on the secondary market for their current value. (This might not matter if you hold the fund long enough.)

(top)

Balanced Funds

To provide an all-in-one portfolio for those who want a “balanced portfolio” (described above), some mutual funds combine group investments of stocks and bonds and portfolio rebalancing to manage a complete portfolio in a single investment. The investor just chooses the fund, and the fund manager does both the investing and the rebalancing.

This is the approach I ended up with in our RRSP and TFSA investments as we approached retirement.2

(top)

Exchange-traded Funds (ETFs)

Later on (I think it was the 1990s) Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) were developed as a variation on mutual funds. ETF shares are bought and sold on stock markets as if they were stocks. They tend to have lower fees than traditional mutual funds. There are many choices, but most ETFs are Index Funds.

I think ETFs are more popular now than traditional mutual funds, due to their lower fees (resulting in higher net return) and easier access.

A particularly interesting class of ETFs is the “asset-allocation” fund. This is a refinement of the “balanced” mutual fund that allows the buyer to select a fund representing the desired asset mix (stock vs bond) along with a mix of markets (Canadian, American, and various other international markets). This can result in a very broad, diversified range of holdings.

Our investment portfolio before and since retirement has been a single ETF. Vanguard Conservative ETF Portfolio (VCNS) is 40% equity (13,643 different stocks) and 60% fixed income (18,606 different bonds), with a “management fee” of 0.22%. (That’s pretty inexpensive.) This has given us a broad mix of investments, all balanced to suit us and requiring no maintenance or tweaks. We could probably do better, but we’ve done all right.

(top)

Conclusion

This article was a lot harder to write than I expected. It’s a big topic, and I don’t know as much as I thought I did. But I think it’s important to understand in general terms how one might hold on to some of one’s money and make it last a lifetime.

The next article I have planned is an introoduction to financial planning — managing money for immediate, short term, and long term future.

(top)

- In fact, though, you’ll probably still want to rebalance your portfolio after taking money out, because you want to keep yourself positioned for the long term. ↩︎

- But as I mentioned in last footnote, I’m having second thoughts about this. Although in the long term (saving for retirement) I think it served us well. ↩︎